By Max Gammon MB BS

Summary

I would like to begin with two propositions that I hope will be obvious to many, if not most readers:

- administration does not necessarily involve bureaucracy;

- bureaucracy does not necessarily involve administration.

In this paper, evidence will be presented that suggests that increasing numbers of National Health Service (NHS) staff, irrespective of their designated function, are spending increasing amounts of time engaged in bureaucratic activities not directly related to the care and treatment of patients, leaving fewer available for that purpose.

British Hospitals Before The Inception Of The NHS

No new hospitals were in fact built during the first thirteen years of the NHS.

Bed Losses And Growth In Numbers Of Staff

A total of 544,000 beds in voluntary and local authority hospitals were taken into the NHS in 1948. By 1973 the number had fallen to 491,000. Beds per thousand of the population had fallen from 11 to just under nine.

NHS 1974-1985

Accelerating bed losses and growth in numbers of staff Between 1974 and 1985 the number of NHS hospital beds in England fell by 71,000 from 396,000 to 325,000 (18 per cent), an average loss of 6,400 beds per year compared with an average loss of 2,000 per year for Britain as a whole between 1948 and 1973.

Bureaucratic Displacement

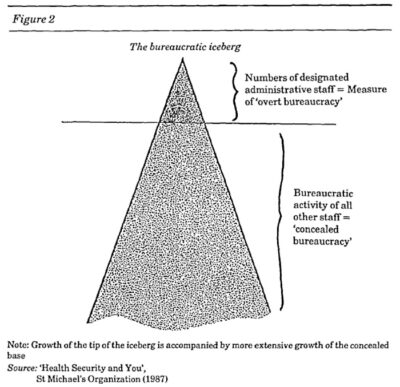

It is important to note that it is not suggested that the growth in numbers of designated administrative and clerical staff is, in itself, of major significance in the dissipation of NHS resources. The theory proposes that this growth is significant primarily as an indicator of a changing pattern of activity, involving the bureaucratisation of the service as a whole ('concealed bureaucracy'). (See Figure 2.)

The bureaucratisation of the nursing profession The growth of concealed bureaucracy is well illustrated by changes that have been occurring in the nursing profession, notably since the implementation of the Salmon Report 8 in the late 'sixties and early 'seventies.

Conclusion

The greatest tragedy in the NHS does not lie in the loss of nearly one-third of Britain's hospital beds built up over many generations, a loss of national resources that will take many years and require huge expenditure to remedy. Nor does it lie in the increasing numbers of patients waiting ever longer for hospital treatment, though their suffering is sometimes appalling and can never be compensated.

The greatest tragedy in the NHS lies in the damage that the system has done to the nursing profession, the medical and allied professions and the profession of hospital administration.